Mental Ecologies of War: A Conversation

From E-Flux

Lukas Brasiskis, Olexii Kuchanskyi, and Elena Vogman

eeefff, Tactical Forgetting (still), 2023.

On the occasion of the launch of Mental Ecologies of War, a new online program curated by Olexii Kuchanskyi and Elena Vogman for e-flux Film, Lukas Brasiskis conversed with Kuchansky and Vogman. The program launches on Wednesday, February 15, at 1 p.m. EST with a live introduction and discussion with the curators, and the performative walk Contemporary History of Ukraine (2023) by Oksana Kazmina. You can find it here.

Lukas Brasiskis: Let’s start by talking about the title of this program. Could you please unpack the meaning of it? One could speculate that it has a connection to Felix Guattari’s “Three Ecologies,” specifically the third, “mental ecology,” which, according to Guattari, is the ecology of human subjectivity. He argues that traditional ways of understanding the self and one’s place in the world are ill-suited to addressing ecological problems, which is why new forms of subjectivity are needed. Is there a connection here? And if so, what does the concept of mental ecology mean in the situation of the ongoing war?

Elena Vogman: You are right in pointing out the importance of Guattari’s concept in developing the focus of the program. Guattari has extended the understanding of ecology far beyond environmental concerns. But I think there is more to it. By including human subjectivity in its mental and unconscious dimensions, but also social relations, into the realm of what he called “an ecosophy,” Guattari shows that subjectivity can be an object of erosion and extraction via the homogenizing mass-media regime.

Olexii Kuchansky: For us “mental ecologies” was first a useful concept to critically address a certain inertia inherent in the discourse around images, which has experienced a true inflation in recent decades. Speaking of “images” that surround us neglects their capacity to create ecologies and fuel economies, to produce what Guattari calls “existential territories.” These milieus are not merely carriers of information or affect, but impersonal architectures of subjectivity, sluices of desire.

EV: What I think is also crucial today, in a situation of mediatized wars, is that the notion of mental ecology provides us with a tool to describe environments beyond national territories that can be toxic, spread nationalisms, or exercise imperial and (neo)colonial power. Extending his thinking of “machines” as couplings of the human and the technological, the notion of mental ecology brings Guattari’s psychoanalytic and psychiatric practice to an environmental and social scale: not only in order to address the mediatized parapolitics of today’s nation-states, but also and especially to reimagine our mental and psychic geographies, to reinscribe bodies as singularities into alternative mentally and socially constituted maps.

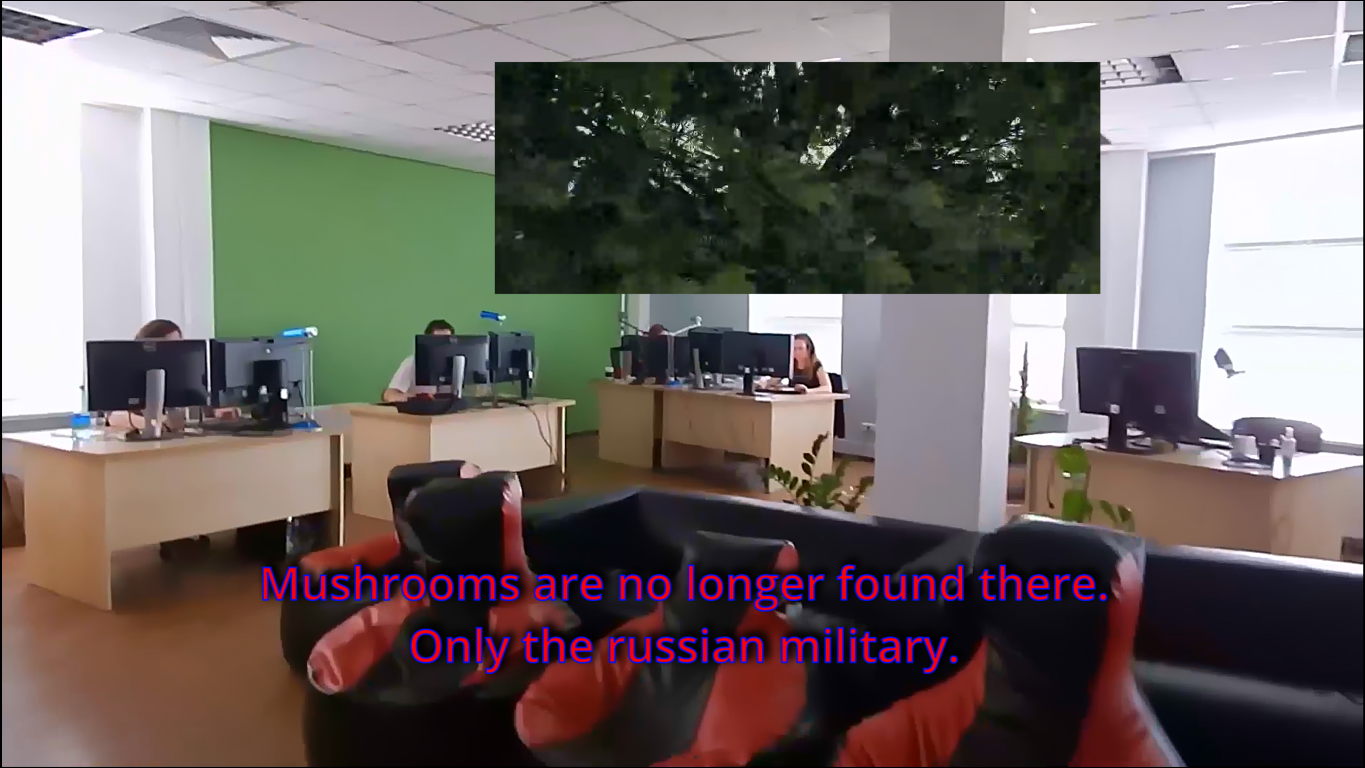

Sashko Protyah, My Favourite Job (still), 2022.

LB: How did it happen that you started to work on this program together? How did your interests coincide in this project?

EV: We were aware of each other’s research and curatorial work before we met in person last September. There were already a number of affinities, such as Marxist approaches to enviromentality and mediality, feminist and decolonial perspectives on Soviet and post-Soviet histories, critical work with archives, and engagement with philosophies of immanence and affect. But the idea of the program emerged from the exchange we had following my visit to Olexii’s really stunning exhibition at Coalmine in Winterthur, “To Watch the War: The Moving Image Amidst the Invasion of Ukraine (2014–2022),” cocurated with Oleksiy Radynski. This show approached moving-image works as seismographs of alternative social, affective, and geographical relations which are completely absent from the globally mediatized geopolitical map. But they are also absent from the majority of artist films with a capital “A.” Working for a while on topics such as “cinema by other means,” and the media and politics of madness, I was particularly astonished to discover this shared subjacent dimension in our respective engagements with moving-image works—what we called, with Guattari, “mental ecologies.”

OK: And this reimagining of mental and psychic geographies is surely instigated by the war conditions, in which our program was developed. Russia’s war on Ukraine is one of the cases when understanding the war also means reconsidering imaginary relations to an earth (geo)—or as I would rather say, to earths. These imaginary relations to earths might be recognized not only within the informational warfare or mediatized parapolitics that install extractivist axiomatics into social processes (for instance, the construction of Nord Stream 2, largely legitimized by mass media). They are also implicit in popular situated practices, as well as in those of activists and artists—like those presented in this program. That is why Guattari’s concept of mental ecologies turned out to be useful. It is a tool to avoid a unifying extractivist geographical frame, which operates within the quantified territories of nation-states. We wanted to avoid this frame in order to explore and proliferate multiple embodied mental ecologies that are marginalized by dominant protocols of the circulation of images.

But getting back to your question. When I discovered Elena’s book Dance of Values: Sergei Eisenstein’s Capital Project (2019) a couple of years ago, I was astonished by the radically nuanced political positioning of this research. It goes beyond any framings of national cultures and the dominant geographical matrix of theorizing the Soviet avant-garde (usually addressed as the “Russian avant-garde,” whatever that means). I think that both of us are interested in a critical approach to the dominant (academic or popular) geographical imaginaries, as well as in the social and political impacts and conditions of our own research and curatorial practices. Thus, we aimed to keep this double focus while working on the program too. Obviously, this altering of the geographical approach requires an alternative approach to a medium—as a milieu of interrelated mental, social, and environmental processes rather than as a pure means of information exchange.

LB: For the first online part of the two-part program you have selected very diverse, multi-genre or rather non-genre moving-image works: from artists’ videos and performative interventions (Oksana Kazmina), to videos shot by a teenage blogger (Alena Zagreba), as well as the work on tactical forgetting and digital memory by the Belarusian collective. What were your criteria in selecting these diverse works for the online program?

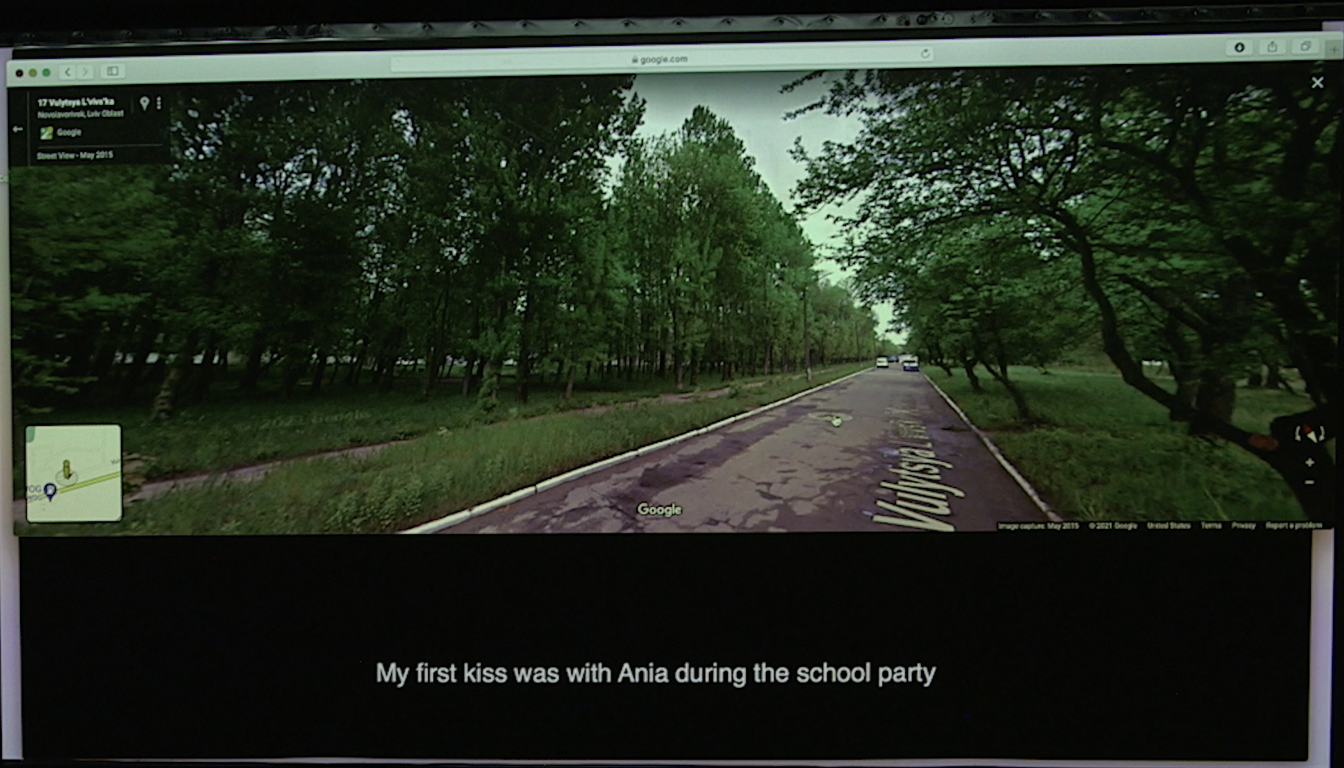

EV: Insisting on moving-image works as vehicles within our mental and social milieus, we were specifically interested in their situatedness as experiments (and experiences) inscribed in trajectories of production, distribution, and perception. This question cannot be determined merely through the aesthetic qualities of the image or its reception in the frame of the contemporary art market. We were trying to track, as Olexii just said, how under the extreme conditions of war certain works transformed their quality of medium into a concrete milieu: a set of relations which retrace a territory, reconfigure the gaze, reinscribe a relation. Oksana Kazmina, for instance, works with a desktop archive and Google Maps to create a geography of drifting in which intimate moments with friends, memories of abandoned places, and contingencies of a performance create a counter-geography to impersonal geostrategic navigation systems.

OK: The case of Alena Zagreba is also very interesting. The diaristic inscription of everyday life events traces the catastrophic war scenario in Mariupol. The Freefilmers collective intervenes into the distribution circuit of bloggers by translating the video diary by Alena Zagreba into several languages and distributing it through different channels. Heterogenesis is a crucial principle that is inscribed into the genesis and the trajectories of these works. It produces alternative—transversal—social relations and mental milieus beyond the homogenizing and toxic media landscape. They operate through experimenting with the very conditions of production, in-between different genres, circulation spheres, and social groups.

Oksana Kazmina, Сontemporary History of Ukraine (still), 2023.

LB: In times of modern warfare, images inevitably serve the mechanism of propaganda (I use the term without negative connotations here). Images of the destruction wrought by Russia on the defenders of Ukraine and, even worse, on the Ukrainian civilian population are being disseminated to highlight war crimes in the making. As a result, popular media screens are flooded by utterly sad and distressing images of atrocities. In contrast, the works presented in the first part of your program focus more on the imagery of mundane experiences of war absent in the mass media. Was this an intentional curatorial decision? If so, could you tell us more about the role of image-making during the war, and what intervention this program is intended to make?

OK: In contemporary global warfare, preoccupied with analyzing, processing, and weaponizing data, cognitive combat has become the latest trend in the art of war. This term designates the usage of the enemy’s cognition as an operational field that can be influenced with tactical means, then modeled to achieve certain strategic goals. Cognitive combat is practiced by the military sector and also by terrorist groups. Such cross-sectionality reveals a crucial feature of contemporary armed conflicts: they are not limited to military operations between armies, but are capable of influencing several sectors of social life (including the production of facts by mass-information machines, collective emotional events, and electoral tendencies). The distribution of weaponry, humanitarian aid, and financial support, and the loyalty of the population of the Russian Federation to the “special military operation”—or, to be more precise, the impossibility of popular resistance—are highly dependent on the tonalities of processed cognition.

EV: I think there is now at least a century-long, and still controversial, debate around shock-images, maybe in a way related to the fact that the media actively participate in warfare, as you say. Mass media and the wars of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are so closely tied to each other that the technological development of vision and mediation is directly incorporated in modern warfare. Weapons of destruction efficiently use imagery as operational images. At the same time, today’s wars enter Telegram channels and circulate on social media almost in real time. These become not only sources for mass media such as state television channels or radio but also influence political decision-making. However, the works in the program deal with different processes that no longer aim at deconstructing, estranging, or enlightening such toxic circuits. They rather offer alternative environments with different conditions of affective stimulation. They recreate the singularity of experience in the formation of these new milieus, in the construction of new spatial and temporal coordinates beyond patriarchal, phallic, and militarized discourses that erect and fuel the war machinery.

OK: In regard to our program, we wanted to avoid any moralism or paranoia, which is implicit in the processes of cognitive combat and its inherent production of an “outside observer” and “objective report”—these processes are no less corrupted by private economic interests and the will to geopolitical domination, even though this corruption is symptomatically blurred by war machinery. We aimed to follow and proliferate experimental approaches to moving images that install immanent coordinates of ongoing events, that produce operational modal differences within minor mental ecosystems. This may involve the invention of these coordinates in real time as the traumatic events are experienced and articulated through available technological means. The immanence we are talking about is far from being a merely personal perspective; it may be defined as a recursive inherency that belongs to the social, political, economic, and aesthetic processes themselves. For instance, My Favorite Job (Sashko Protyah, 2022) is not only a documentary about volunteers who evacuate people from Mariupol, but also a film that consists of images produced by volunteers. Furthermore, since the licensing fees are shared with the volunteer organization, and the filmmaking team does volunteer work (even now), they also take into account such pragmatics, so the film itself can be considered as a chain of volunteering infrastructure. That is also why—coming back to your previous question—the presented practices are so formally diverse: it is due to the multiple milieus in which they operate.

Alena Zagreba, 2 weeks of hell in 7 minutes–video diary from Mariupol (still), 2022.

LB:: Wars produce traumas, and imaging them is often considered to be one of the strategies to cope with trauma. However, some theorists have made an ethical argument against the mediation or representation of traumatic experiences on film. While designing this program, did you regard the ethical and philosophical debate over the representability/non-representability of traumatic experiences important? It seems to me that the selection of videos argues against the Cartesian dualism between mind and body and the constraints it places on understanding/imagining the state of war. How do these works suggest a new mental environment?

OK: It is definitely true that reconsidering the body is crucial for artistic approaches, especially within the “Bodies, Subjectivities, Milieus” part of the program. In our conversation,

Dana Kavelina pointed out that the female body at war is treated as a text to be exchanged between warring parties through rapes and “liberations.” I think that this awareness of neglected violence comes from a completely different understanding of media and the body than the understanding found in the representability/non-representability debate. The significant accompaniment of this understanding is a recognition of already existing practices that are preoccupied with adapting aesthetic, discursive, and technological means to include bodily states and traumatic experiences into the socius rather than to simply isolate them within strategies of representation. For instance, in Sashko Protyah’s Film of Sand, the externalized erotic haptic visuality of touching and caressing the beach distills the haunting audio interruptions of the Russian army’s homophobic radio messages. It does not ignore them, but undermines despair as a state of affective occupation. The other case is Halyna Yarmanova and Svitlana Shymko’s The Wonderful Years, which is concerned rather with a structural element of ongoing war: gender captivity by social protocols of behavior. It is an audiovisual research project exploring the lives of queer women in Ukraine in the late Soviet Union based on archival video materials and interview excerpts from several research projects. The film shows how these women found ways to avoid social and state pressures to marry and have kids, navigating a dating life outside marriage, choosing to stay single, or cohabitating with women. To recognize the agencies of bodies means to accept that being oppressed is not limited to being a victim.

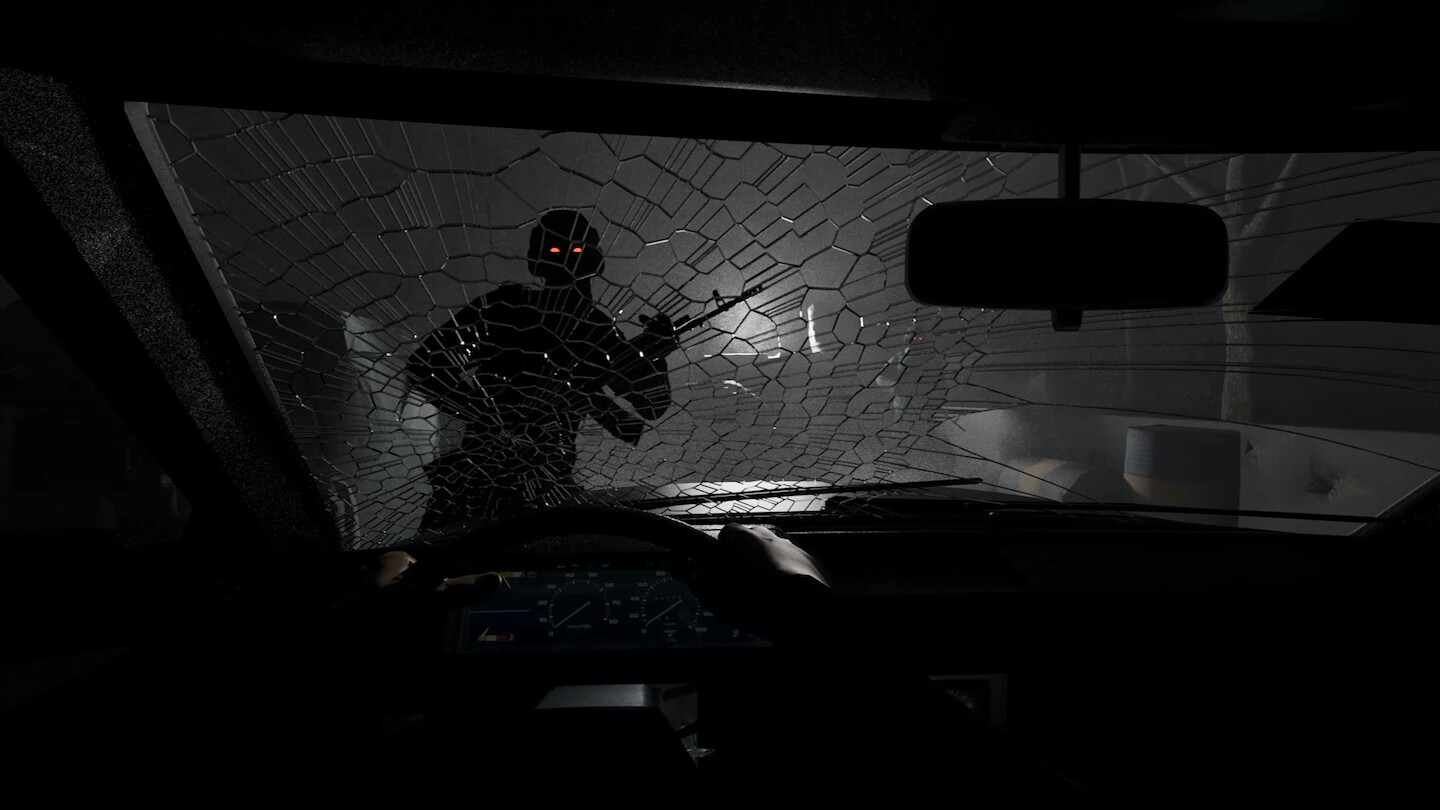

EV: I think the question of representation, such as representing a national war or a specific social group as its victim, was not central to our reflection on the program. However, we were very concerned with the question of trauma and the ethics of moving-image production. But we tried to address these questions as simultaneously situated and entangled. Guattari’s concept of mental ecologies is a result of his life-long psychoanalytic and psychiatric practice, a practice of politicizing mental processes by reconnecting these with social, ethical, environmental, aesthetic, and even architectural concerns (for instance the exclusion of madness from society requires carceral institutions situated in specific geographies). To give you an example, in Sashko Protyah’s film My Favorite Job we see a computer-generated landscape from the outskirts of Mariupol that simulates the trajectory of people fleeing the war zone. Taking images on this dangerous path posed an additional threat since every image could be used as an evidence of war crimes committed by the Russian army, and was thus brutally suppressed by them. The absence of documentary footage here is crucial, and the use of simulation is not a matter of representing the unrepresentable but a significant part of the (image) infrastructure. Furthermore, these geographies are a decisive element in the work of activist groups helping people to flee the city. We also see very unusual witnesses in this film. People who escaped the city full of dead bodies speak of their experiences while bursting out laughing. The witness speaking of terrifying things is interrupted by spasms of laughter. Such expressions of emotion dialectically recompose the body, not only of the speaking subjects but also of the audience. They introduce a radical difference into certain clichés and conventions of representation, and expose the incredible complexity of traumatic processes as such, their temporalization, and their social and collective inscriptions.

OK: Yes, and that is also why we maintain that certain moving-image practices are not simply messages, but a multiplicity of social weavings that extend, process, explore, and reinvent the war-influenced milieus. Besides many other sources, our program draws from a film program called Forced Displacements and Moving Images. This took place in Lviv in March–August 2022, when many internally displaced people, including artists and filmmakers, came to that western city of Ukraine, which was significantly safer in those days. In the new war conditions, artists, displaced art students, international volunteers, and migrant cinephiles attempted to reassemble our imaginary environs and collective mental relations via the screen, exploring and reinventing the surroundings of the temporary transregional city of Lviv. The program was mostly based on filmic practices about places, situations, and communities that were disrupted by the Russian invasion: the beach on the Sea of Azov, the outskirts of Mariupol, underground parties thrown by Kyiv’s electronic music community. Obviously, nobody thought of representing trauma, because, firstly, the traumatic experience was (and still is) unfolding; and secondly, it was impossible to distinguish between the imaginary production of a new habitat and the re-presentation of lost and destroyed spaces, including the traumatic experience of this loss. Hopefully, despite many obvious differences, Mental Ecologies of War follows the same intention to participate rather than to inform or to represent.

LB: Could you tell us more about your interactions with the singular and collective authors of these films and videos? Do they see these works as art or more as information, and how do you, as curators, see them? And, more broadly, what are the main challenges that Ukrainian artists residing in Ukraine face during the war?

EV and OK: If you don’t mind, we would take a step back and relate this question to our earlier discussion about the interrelation between production, distribution, and perception. While preparing the program we noticed a tiny detail, which reflects the condition of contemporary Ukrainian filmmaking and moving-image practice. We mean the impossibility of having fast communication with artists or even receiving files with films that meet the requirements of the screening platform. This happened due to the blackouts and the wider destruction of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure by the Russian Federation’s massive rocket strikes. This technological issue conditions contemporary art coming from Ukraine.

Blackouts are not the only reason for low-res images, raw edits, unfinished thoughts, and incisive and even radical hints rather than detailed statements. In addition to the pressing need to arrange new material conditions for artists’ work and everyday life (due to closed institutions and the destruction of workspaces), we have to consider the colonialist conditions of artistic production in Central-Eastern Europe, which was highly centralized by Moscow and St. Petersburg, and, since 1991, by American and West European capitals as well. The frustration of many art institutions last year, which wanted to react to the escalation of war in Ukraine, when whatever-on-Ukraine was extensively exhibited, is also related to this centralization. There are simply no material means to differentiate and institutionalize in a proper way the diverse artistic approaches and thematizations from Ukraine—though we strongly believe that this condition is not only oppressive. As can be seen from the practices presented in our program, there are also, paradoxically, multiple potentialities for political subversions and re-singularizations of subjectivity.